Fanworks

Goal

Based on the given brief: to design the Information Architecture of a web-based information environment.

I chose the topic of fanworks with the goal of creating a website that could bridge the disconnect that forms within fandoms because of their spread across the internet.

I chose the topic of fanworks with the goal of creating a website that could bridge the disconnect that forms within fandoms because of their spread across the internet.

Tools

Figma, Optimal Workshop, Remote Interview Moderation (Microsoft Teams) and Recording (QuickTime) Software

Introduction

This was one of my favourite projects I completed during my degree; I really enjoyed organizing complicated information into something usable.

While there were some restraints on the project (i.e. the number of wireframes and the word count), the approach was up to me to justify.

For each of the following sections, I have included the corresponding deliverable (all were made in Figma) and snippets of my design justifications.

For each of the following sections, I have included the corresponding deliverable (all were made in Figma) and snippets of my design justifications.

Interviews

Three Domain Experts were interviewed.

This established that, while my topic was fanworks, fandoms themselves dictate which fanworks hold value.

These experts also emphasized the importance of the ability to block/exclude certain filters/tags.

Website Review

An informal review of the well-known fanfiction website Archive of Our Own (AO3) was also performed.

AO3 was useful as a database and as a way of understanding how people customize their fandom experience through user-generated tagging.

Overlap in Data

Overlap between AO3 and expert interviews helped make it possible to determine which elements were expected across fandoms and fanworks.

And because fans shape their fandom experiences, it was expected to prioritize folksonomies over structured data (Rosenfeld et al, 2015, pp. 128).

Domain Model

The overall goal of the Domain Model was to identify core concepts and their relationships between each other.

I saw building off of the Hub and Spoke structure that focused on a “central concept” (Brown, 2011, pp. 80) as the best approach to accommodate the diversity that exists across fandoms.

But these diverse elements are still interconnected, making Brown’s advice on “reducing triangles” a vital way in determining core relationships (2011, pp. 82).

Sitemap

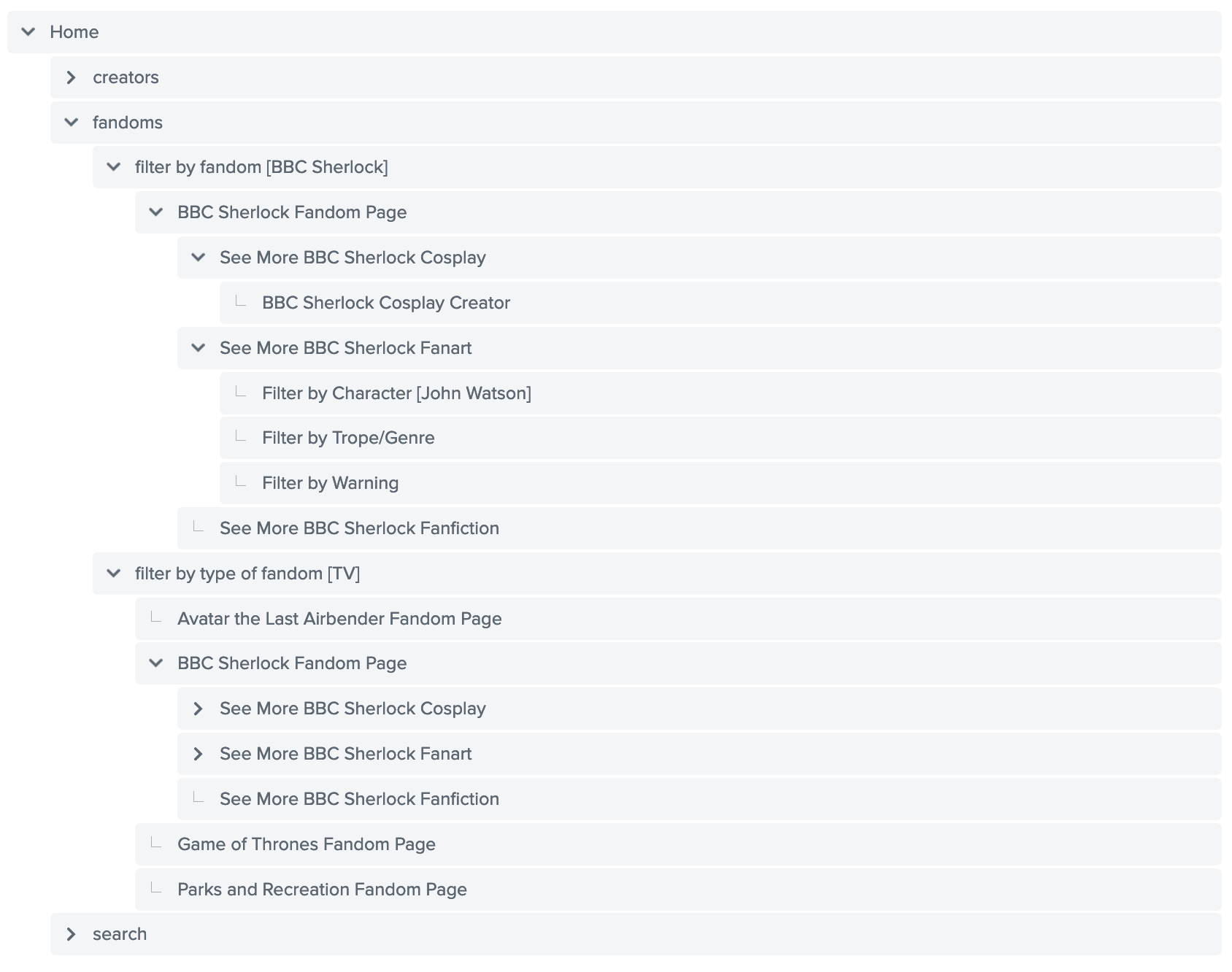

Card Sorting (on Optimal Workshop) was used to see if potential users would be able to condense the 12 types of fandoms from AO3 (alongside others I had added).

Due to the variation in fandom experiences, my hypothesis that this Card Sort might not help refine these groupings was correct.

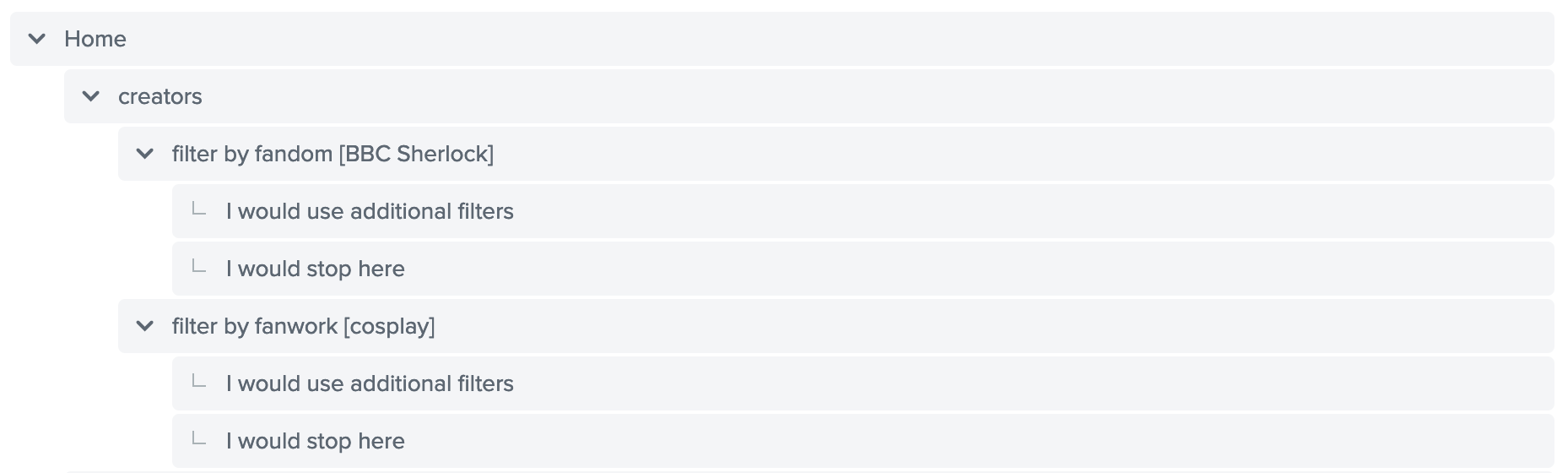

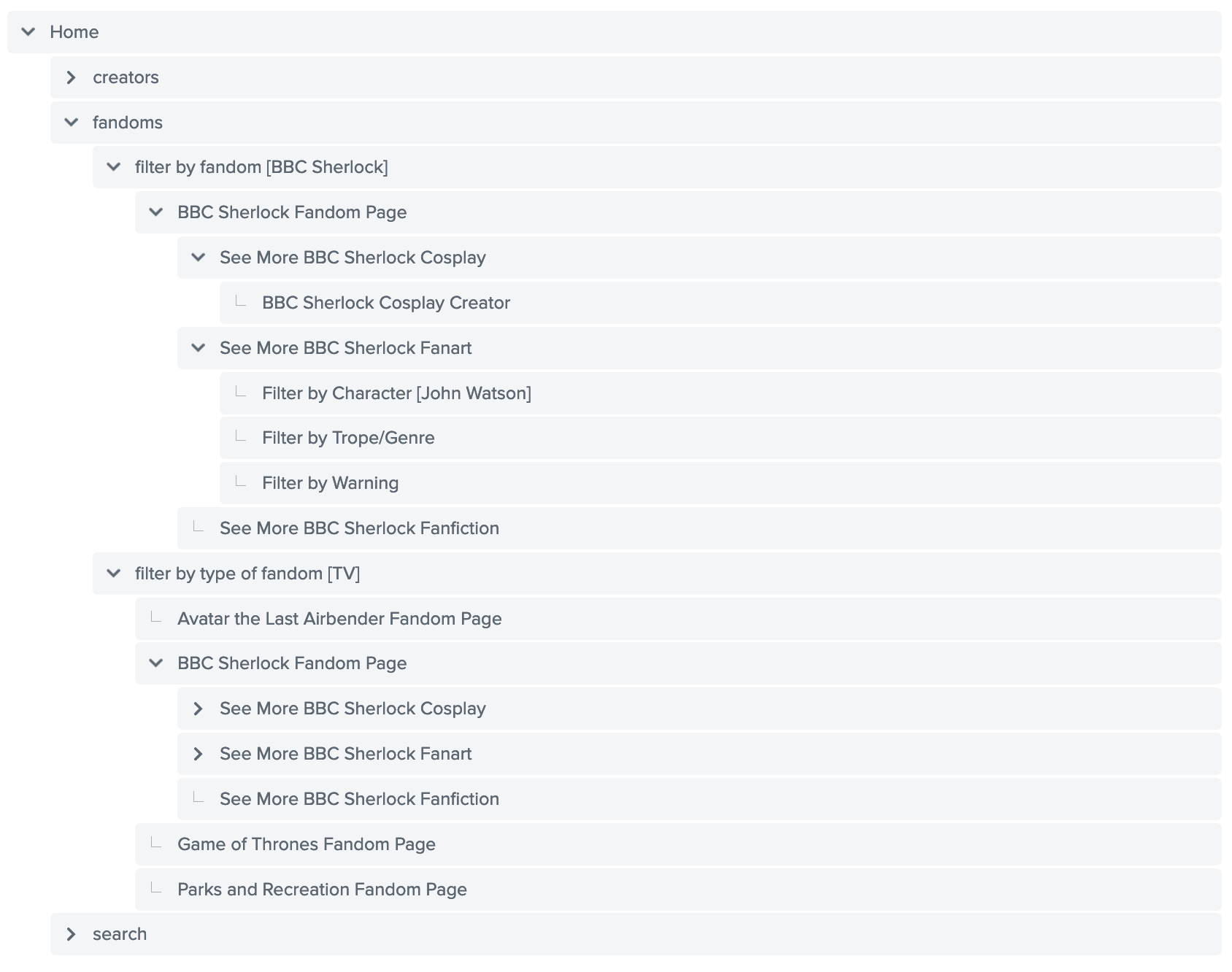

Noticing that the only entities in my Domain Model feeding directly into fanworks were fandoms and creators led to the use of the hybrid Hierarchical and Database pattern as the user would constantly come across “larger volumes of information,” and to drawing upon Spencer’s “basic shapes for drawing an IA,” especially her “part of a page” notation (Spencer, 2010, pp. 180-193, 247).

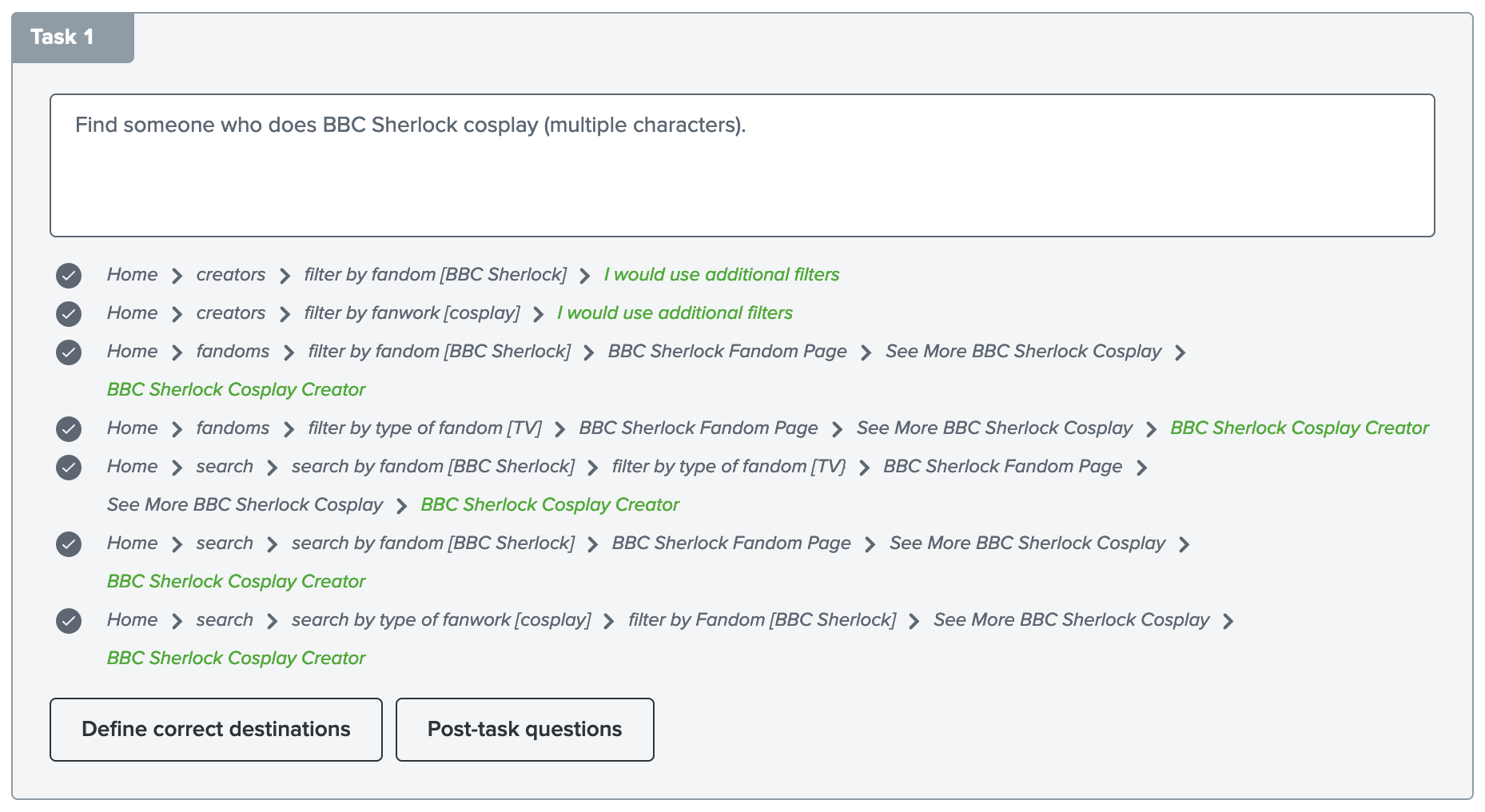

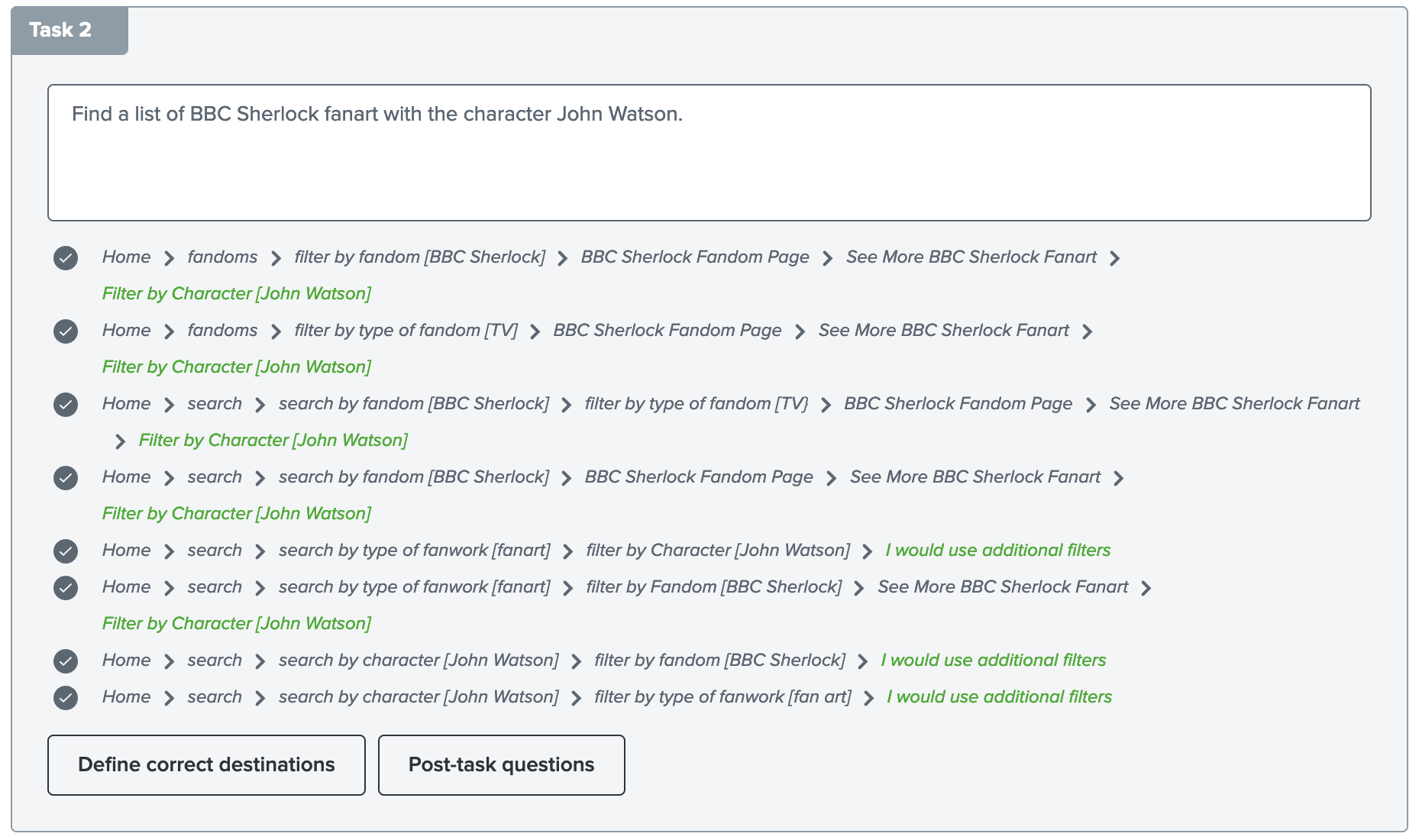

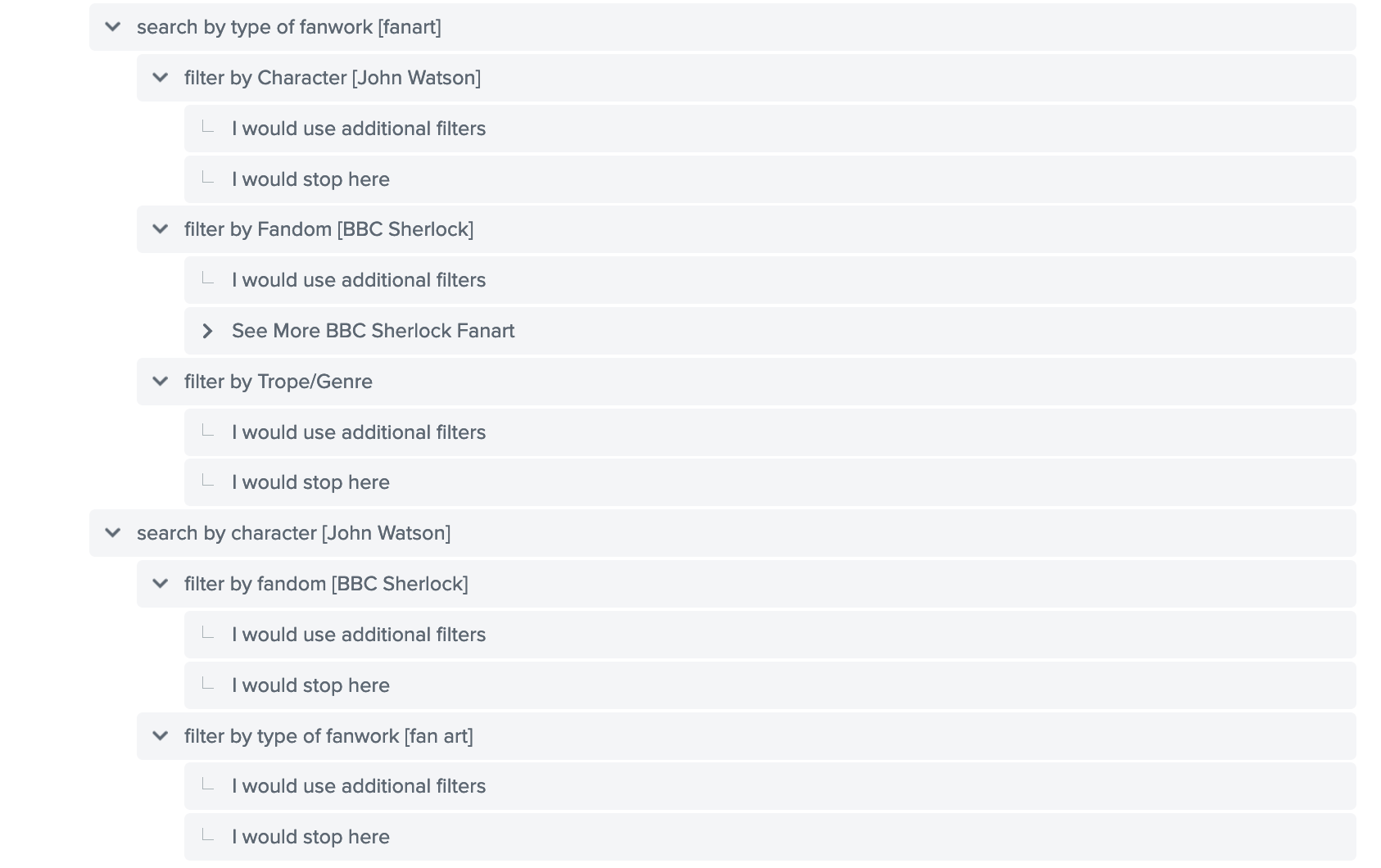

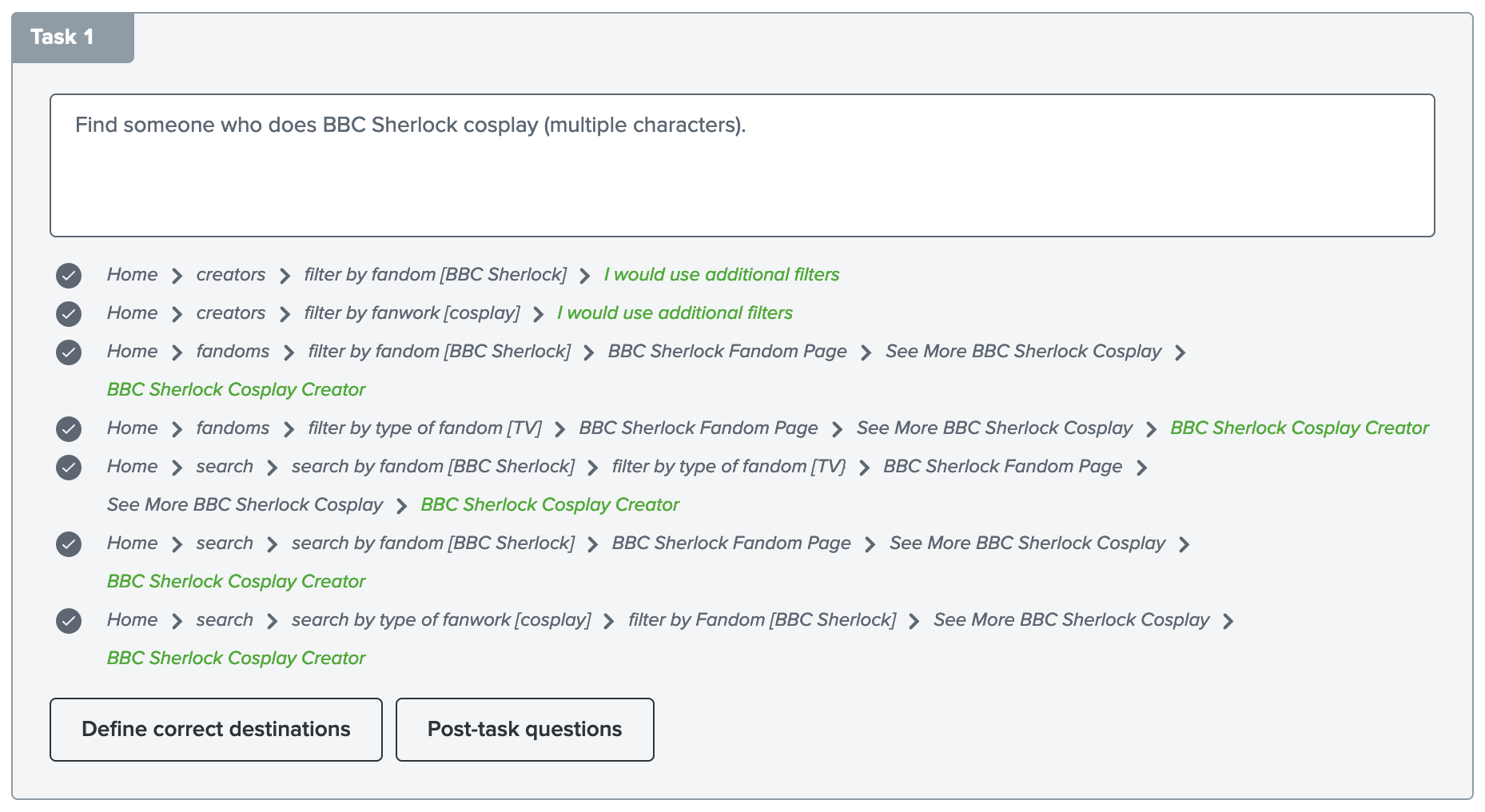

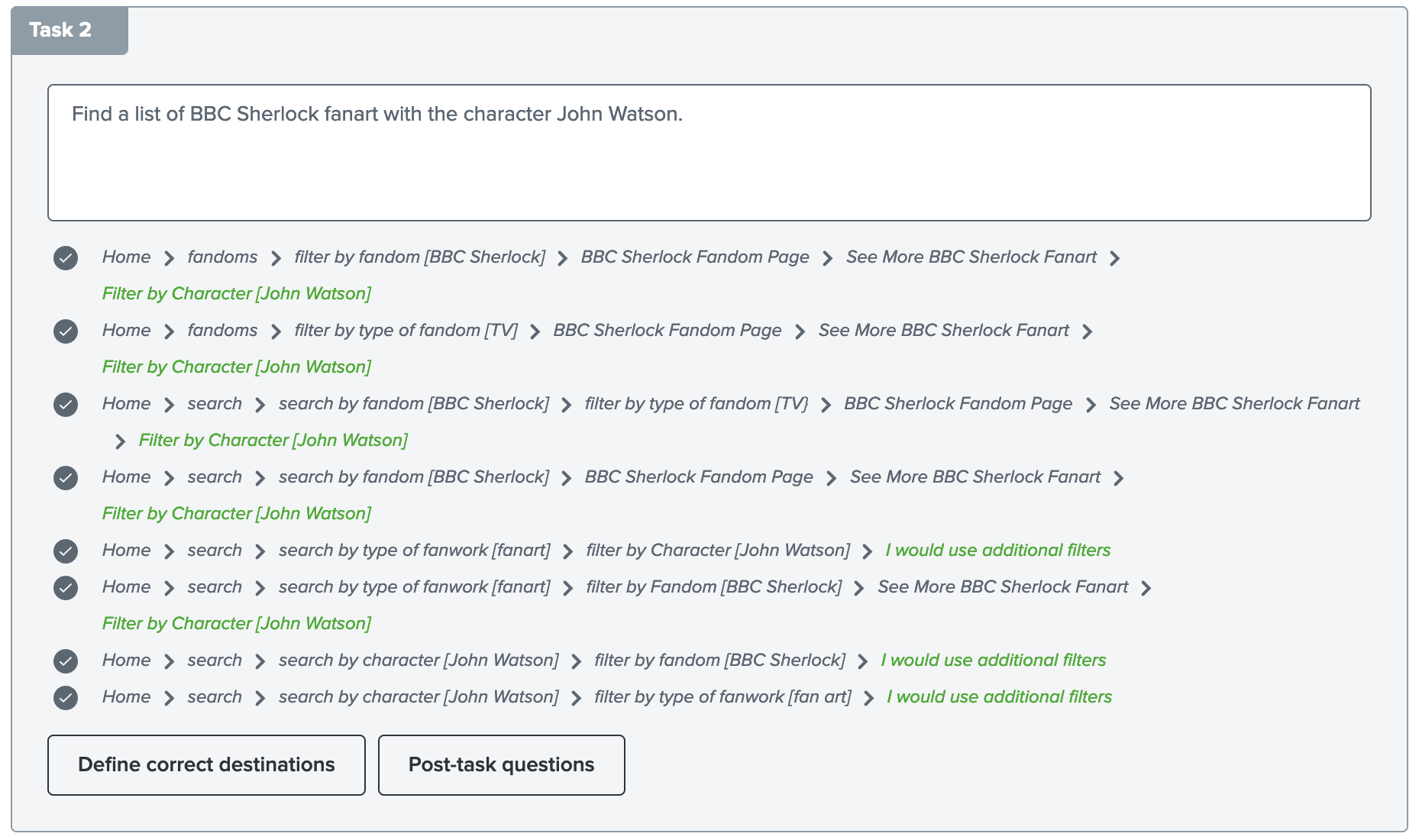

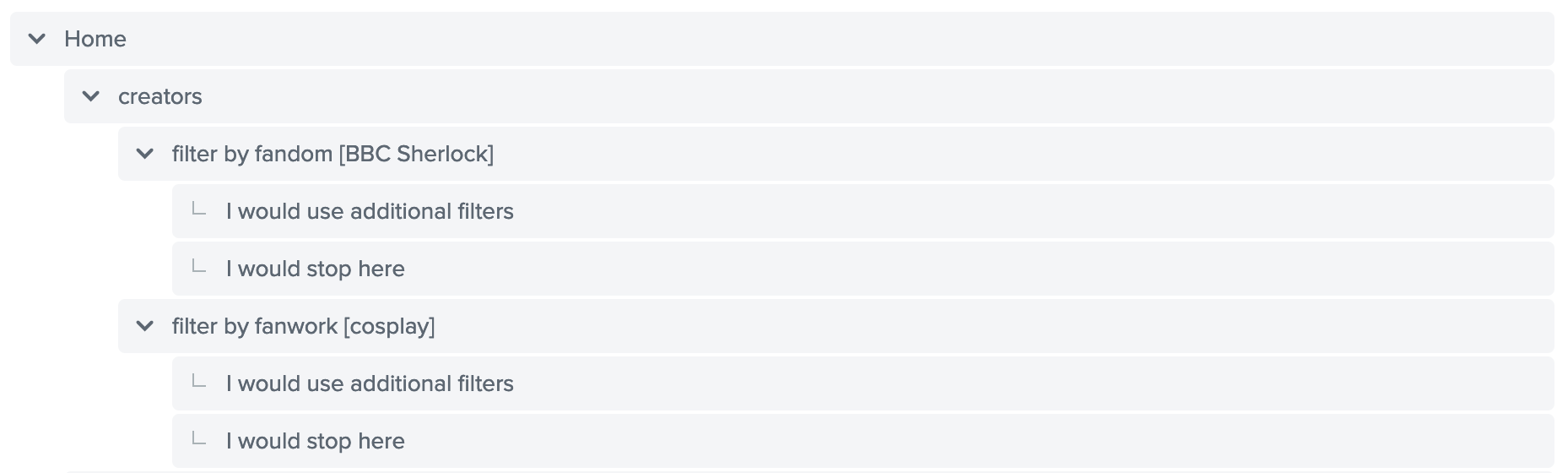

Before moving forward, Tree Tests (on Optimal Workshop) that incorporated filtering and covered all potential paths were performed.

Because 50% of tasks were completed using the “Fandoms” navigation, which would link to thousands of results, that category was broken down so users looking to browse could have a more manageable experience. “Blended Results” exists for a similar reason; each category of result utilizes different facets and showing multiple on the same page could complicate the website for users. Creating this Sitemap allowed me to take the higher level concepts from the Domain Model and think about how they could be perceived from a user's perspective.

Before moving forward, Tree Tests (on Optimal Workshop) that incorporated filtering and covered all potential paths were performed.

Because 50% of tasks were completed using the “Fandoms” navigation, which would link to thousands of results, that category was broken down so users looking to browse could have a more manageable experience. “Blended Results” exists for a similar reason; each category of result utilizes different facets and showing multiple on the same page could complicate the website for users. Creating this Sitemap allowed me to take the higher level concepts from the Domain Model and think about how they could be perceived from a user's perspective.

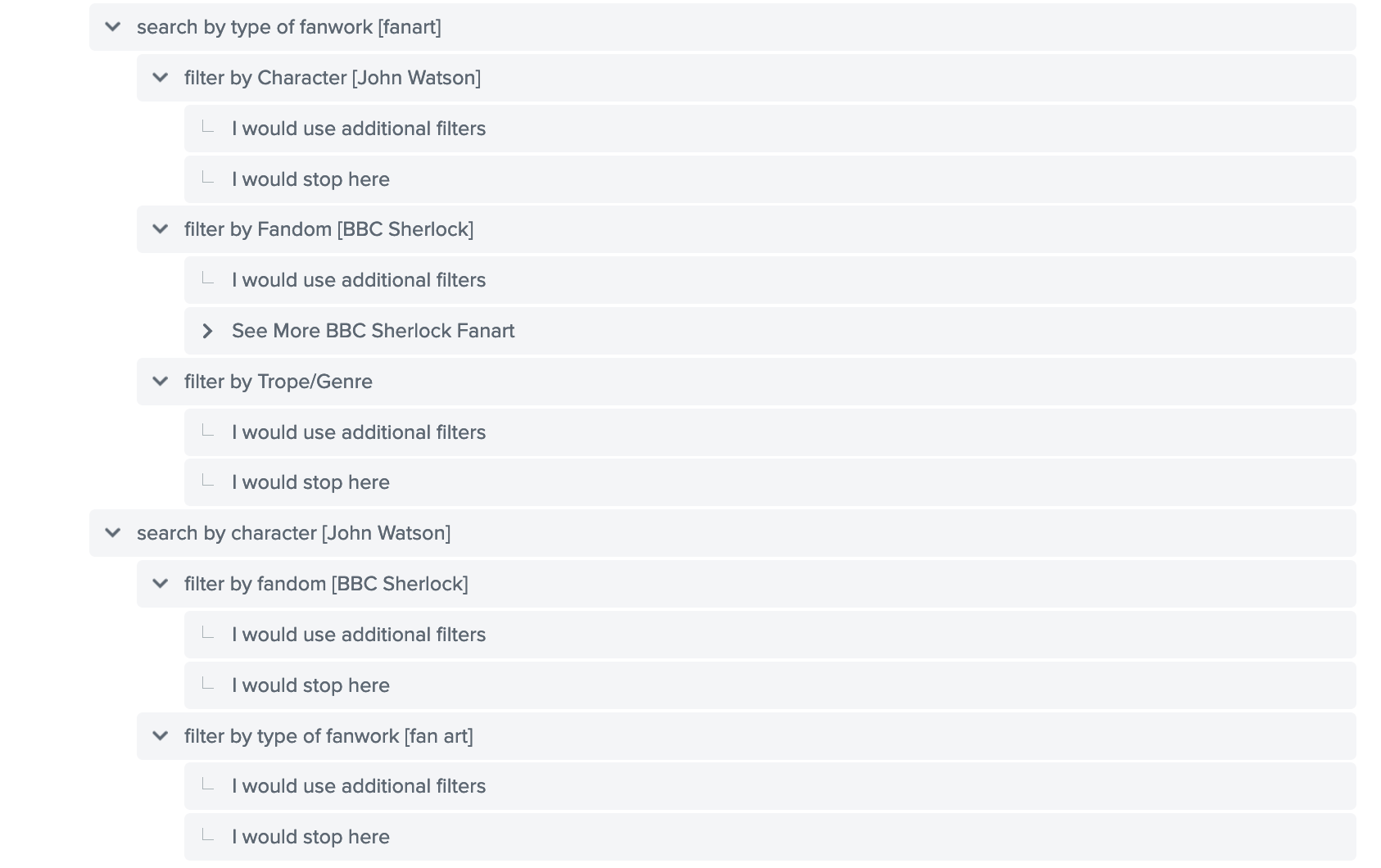

User Journey

Building a scenario helped clarify how a user might incorporate filters.

The journey itself was meant to showcase four potential ways a user could find fanart.

Because every user’s background with fandom is different, only including a preferred path would not showcase the range of options.

However, what could be considered a preferred path based on number of steps and the specific attributes of the user as established by the goal was highlighted.

The User’s Thoughts were added to establish context and help emphasize why this journey might be preferred considering their specific background with the Doctor Who fandom (Brown, 2011 pp. 140). Inspiration was take from Caddick and Cable’s design of diamond shaped decision points and pointed rectangles for steps (i.e. actions) (2011, pp. 83). As they used a rounded rectangle for the starting point (Caddick and Cable, 2011, pp. 83), which in this case was the Home page, rounded rectangles were used to notate any page the user might reach. Making sure not to “cross the streams” (Brown, 2011 pp. 130) helped organize the elements and structure of the journey itself. When a user is making a more significant step forward in the process, they move from left to right, but actions that don’t offer as much change to what the user sees are typically stacked.

The User’s Thoughts were added to establish context and help emphasize why this journey might be preferred considering their specific background with the Doctor Who fandom (Brown, 2011 pp. 140). Inspiration was take from Caddick and Cable’s design of diamond shaped decision points and pointed rectangles for steps (i.e. actions) (2011, pp. 83). As they used a rounded rectangle for the starting point (Caddick and Cable, 2011, pp. 83), which in this case was the Home page, rounded rectangles were used to notate any page the user might reach. Making sure not to “cross the streams” (Brown, 2011 pp. 130) helped organize the elements and structure of the journey itself. When a user is making a more significant step forward in the process, they move from left to right, but actions that don’t offer as much change to what the user sees are typically stacked.

Types of Testing

Remote, Moderated Tests with 3 target users were completed.

A Click Test was also created and posted to Tumblr, targeting online users with a strong interest in fandoms and fanworks; 28 users completed this study.

Questions were formulated with inspiration from Toub’s approach (2000).

To evaluate structure, grouping, and labeling, the goal from the User Journey was used as a prompt.

Questions about initial actions a user might take and what users thought clicking on certain elements would do/show were also asked (Toub, 2000, pp. 14-23).

The Click Test and Moderated Testing results generally aligned; a low success rate from the Click Tests coupled with similar results from the Moderated Tests made a change higher priority.

Annotated Wireframes

Screen 1 - Home

All users during the Moderated Tests were able to vocalize what clicking on “By Fandom Type” would do, confirming this labeling choice. As users leaned more towards navigational breakdowns, future iterations could explore making “Fanworks” a drop-down through the use of Card Sorting to see if overarching categories related to medium could be established. Additionally, further testing would help determine the best options for the “All Categories” drop-down as results from the Moderated Tests were inconclusive. To prevent users from being biased towards clicking on “Fandoms,” the dropdown was not initially shown.

Screen 2 - Blended Results

While users can choose a category “to clarify their intent,” if they do not, because the results would not be “homogeneous,” they will see this Blended Results page (Russel-Rose and Tate, 2013, pp. 144). This approach was appropriate as there is no preferred path users should take as this site strives “to encourage [users] to engage in further exploration and discovery” (Russel-Rose and Tate, 2013, pp. 144). Moderated Testing participants indicated that they liked seeing this page as it made the results less overwhelming.

Screen 3 - All Results

While testing, to prevent bias, all filters were unchecked. The default state of each filter would be collapsed due to their size (Russel-Rose and Tate, 2013, pp. 173-174). “Fanworks, Platforms, and Languages” use traditional, squared checkboxes as users might want their results to, for example, contain fanfiction AND fanart. “Fandoms, Warnings, Characters, Tropes and Genres, and Ships” use a hybrid checkbox and radio button. The circular shape comes from the radio button to imply that an element can be included OR excluded; the check and X come from the checkbox and are used to show that multiple elements within a filter can be selected. Moderated Test participants successfully recognized how these filters would work. Because the list in “Characters” can become long, to limit scrolling, pagination was added and the elements were ordered via popularity (Russel-Rose and Tate, 2013, pp. 150). Since the use of folksonomies and study of tagging on AO3 means the number of “Specific References” could be incredibly large, and considering Russel-Rose and Tate’s explanation, AO3’s “Additional Tags” option, and the importance of inclusion and exclusion, Search Within was used (2013, pp. 103-104).

Screen 4 - Fanwork Page

Intrinsic, administrative, and descriptive metadata (Spencer, 2010, pp. 187) are all used and displayed to offer the user thorough information about any fanwork. However, inspired by the feedback from one of the Moderated Tests (the user felt there was not enough focus on the image), a Five Second Test could be used to see what information users are drawn to on this page (Booth, 2022) and then, once they have had more time to look at the page, ask them if that information aligns with what they value most. When asked where to find more information about the creator of this fanwork, 82% of Click Test participants clicked on “I_Met_DT” (expected) and 11% went to the Tumblr link. In the Moderated Tests, users went to “I_Met_DT,” Tumblr, or to Tumblr and then back to “I_Met_DT,” if unsatisfied. Future testing, could be used to determine if showing users a Creator page before this one would prompt more of them to remain on this website.

Booth, T. (2022) ‘Week 10 Evaluating Information Architectures’ (Lecture Notes) INM401 Information Architecture. City, University of London. 7 December.

Brown, D. (2011) Communicating Design Second Edition Developing Website Documentation for Design and Planning. Berkley, California: New Riders.

Caddick, R. and Cable, S. (2011) Communicating the User Experience A Practical Guide for Creating Useful UX Documentation. West Sussex, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

‘Cosplay’ (2022) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cosplay (Accessed: 29 December 2022).

‘Category: Tropes & Genres’ (2020) Fanlore. Available at: https://fanlore.org/wiki/Category:Tropes_%26_Genres (Accessed: 3 November 2022).

‘Crossover’ (2022) Fanlore. Available at: https://fanlore.org/wiki/Crossover (Accessed: 29 December 2022).

‘Fanart’ (2022) Fanlore. Available at: https://fanlore.org/wiki/Fanart (Accessed: 29 December 2022).

‘Fandom’ (2022) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fandom (Accessed: 3 November 2022).

‘Fanfiction’ (2022) Fanlore. Available at: https://fanlore.org/wiki/Fanfiction (Accessed: 29 December 2022).

‘Fanwork’ (2022) Fanlore. Available at: https://fanlore.org/wiki/Fanwork (Accessed: 3 November 2022).

‘Genre’ (2022) Fanlore. Available at: https://fanlore.org/wiki/Genre (Accessed: 3 November 2022).

Gibbon, C. (No date) ‘What is content modeling’, Cleve Gibbon, (No date) Available at: http://www.clevegibbon.com/content-modeling/what-is-content-modeling/ (Accessed: 10 November 2022).

Organization for Transformative Works. (No date) Archive of Our Own beta. Available at: https://archiveofourown.org/ (Accessed: 1 November 2022).

Organization for Transformative Works. (No date) Symbols we use on the Archive. Available at: https://archiveofourown.org/help/symbols-key.html (Accessed: 30 December 2022).

Rosenfeld, L., Morville P., and Arango, J. (2015) Information Architecture: For the Web and Beyond (4th Edition). Sebastopol, California: O’Reilly Media, Inc.

Russel-Rose, T. and Tate, T. (2013) Designing the Search Experience The Information Architecture of Discovery. Waltham, Massachusetts: Elsevier Inc.

Spencer, D. (2010) A Practical Guide to Information Architecture. Penarth, United Kingdom: Five Simple Steps.

Toub, S. (2000) Evaluating Information Architecture A Practical Guide to Assessing Website Organization. Argus Associates.

‘Transformative Work’ (2022) Fanlore. Available at: https://fanlore.org/wiki/Transformative_Work (Accessed: 3 November 2022). ‘Trope’ (2022) Fanlore. Available at: https://fanlore.org/wiki/Trope (Accessed: 3 November 2022).

‘Warnings’ (2022) Fanlore. Available at: https://fanlore.org/wiki/Warnings (Accessed: 3 November 2022).

Brown, D. (2011) Communicating Design Second Edition Developing Website Documentation for Design and Planning. Berkley, California: New Riders.

Caddick, R. and Cable, S. (2011) Communicating the User Experience A Practical Guide for Creating Useful UX Documentation. West Sussex, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

‘Cosplay’ (2022) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cosplay (Accessed: 29 December 2022).

‘Category: Tropes & Genres’ (2020) Fanlore. Available at: https://fanlore.org/wiki/Category:Tropes_%26_Genres (Accessed: 3 November 2022).

‘Crossover’ (2022) Fanlore. Available at: https://fanlore.org/wiki/Crossover (Accessed: 29 December 2022).

‘Fanart’ (2022) Fanlore. Available at: https://fanlore.org/wiki/Fanart (Accessed: 29 December 2022).

‘Fandom’ (2022) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fandom (Accessed: 3 November 2022).

‘Fanfiction’ (2022) Fanlore. Available at: https://fanlore.org/wiki/Fanfiction (Accessed: 29 December 2022).

‘Fanwork’ (2022) Fanlore. Available at: https://fanlore.org/wiki/Fanwork (Accessed: 3 November 2022).

‘Genre’ (2022) Fanlore. Available at: https://fanlore.org/wiki/Genre (Accessed: 3 November 2022).

Gibbon, C. (No date) ‘What is content modeling’, Cleve Gibbon, (No date) Available at: http://www.clevegibbon.com/content-modeling/what-is-content-modeling/ (Accessed: 10 November 2022).

Organization for Transformative Works. (No date) Archive of Our Own beta. Available at: https://archiveofourown.org/ (Accessed: 1 November 2022).

Organization for Transformative Works. (No date) Symbols we use on the Archive. Available at: https://archiveofourown.org/help/symbols-key.html (Accessed: 30 December 2022).

Rosenfeld, L., Morville P., and Arango, J. (2015) Information Architecture: For the Web and Beyond (4th Edition). Sebastopol, California: O’Reilly Media, Inc.

Russel-Rose, T. and Tate, T. (2013) Designing the Search Experience The Information Architecture of Discovery. Waltham, Massachusetts: Elsevier Inc.

Spencer, D. (2010) A Practical Guide to Information Architecture. Penarth, United Kingdom: Five Simple Steps.

Toub, S. (2000) Evaluating Information Architecture A Practical Guide to Assessing Website Organization. Argus Associates.

‘Transformative Work’ (2022) Fanlore. Available at: https://fanlore.org/wiki/Transformative_Work (Accessed: 3 November 2022). ‘Trope’ (2022) Fanlore. Available at: https://fanlore.org/wiki/Trope (Accessed: 3 November 2022).

‘Warnings’ (2022) Fanlore. Available at: https://fanlore.org/wiki/Warnings (Accessed: 3 November 2022).